WASHINGTON – The US Senate showed this week that it can still set aside partisan differences and unite for a common goal on some issues. The question is: Daylight saving time.

On Tuesday, the Senate unanimously agreed that it would like to make the annual weather “go ahead” by an hour throughout the year. Now the nation’s clock watchers are waiting to see what the House of Representatives will do with the proposed “sunscreen law.”

Despite overwhelming support for the proposal in the Senate, American views of permanent daylight saving time are far from the norm and some Americans are already casting a shadow over it.

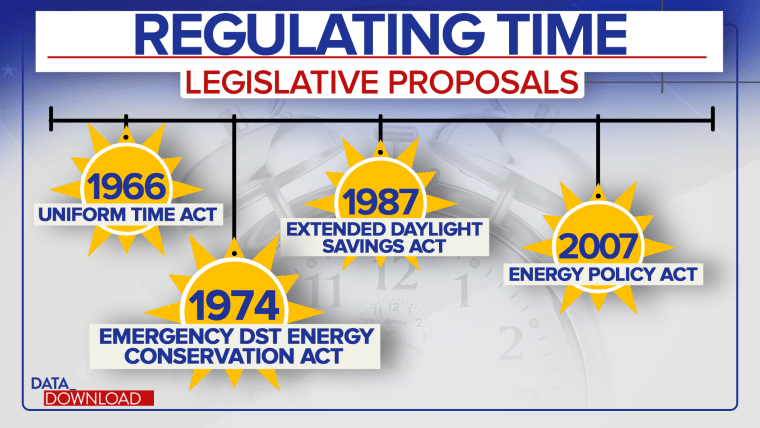

This is not a new area for Washington. Over the past 60 years, there have been more than a few proposals regulating how the nation should set its clocks. Washington even passed an earlier law making daylight saving time “permanent.”

From the end of World War II to the 1960s, there were no national laws about daylight saving time. States and entities within states followed their own rules. Local differences played a corrupting role in the transmission and broadcast schedules, and in response, Washington enacted the Uniform Time Act in 1966, establishing an official schedule for DST with “going forward” on the last Sunday in April and then “backtracking” the last Sunday in October.

In 1974, when the energy crisis was in full swing, the Emergency Daylight Conservation Act went into effect. I made daylight saving time in effect year-round (sound familiar?), for a two-year trial period. But Congress ended the experiment early when people complained about the darkness of winter mornings — especially for schoolchildren — and went back to the old schedule.

In 1987, Washington moved DST to cover the period from the first Sunday in April (instead of the last) to the first Sunday in November (instead of the last Sunday in October)—extending DST by about five weeks.

Finally, in 2007, Washington shocked the days when we change the clocks back to where we are now, set forward on the second Sunday in March and descend again on the first Sunday in November.

That’s a lot of messing around with the watch. Mostly, the movement was toward codification and extension of daylight saving time, except when the public revolted in the 1970s. If the House passed the Senate bill and President Joe Biden signed it into law, would the reaction be different this time? There are reasons to doubt.

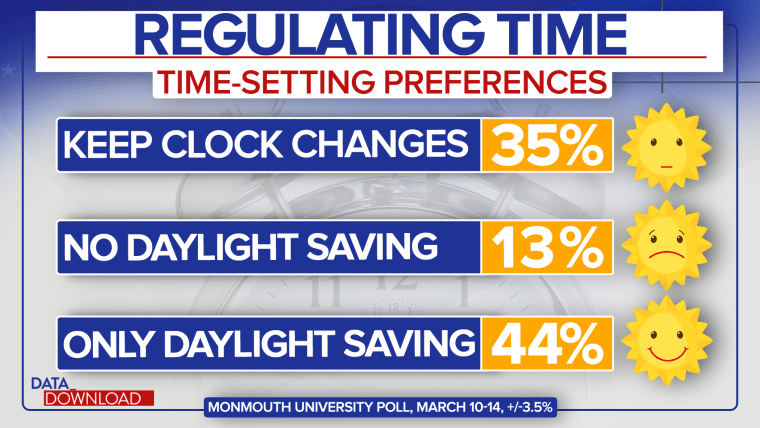

Some people prefer an early sunrise, while others prefer a late sunset. Monmouth University released a poll early this week that showed a split in public opinion.

Altogether, a large number, 44 percent, preferred moving the clock forward throughout the entire year. But 35 percent wanted to keep clock changes as they currently are, and another 13 percent wanted to get rid of daylight saving time and use “standard time” primarily throughout the year.

So, when doing the math, a few more people would rather the bill not be approved by the Senate this week.

And when you add in the latitude where respondents live, the numbers change slightly. People who live above 42nd latitude (which, for reference, makes up most of the border between New York and Pennsylvania) are somewhat more inclined to keep daylight saving time the same.

One reason may be that daylight is a rare commodity in those northern communities during the winter. On January 1st of this year, for example, daylight in Miami was about 10.5 hours. Boston had about nine. No matter what you do with the hours, you can’t change the tilt of the Earth’s axis. And if you live in the North, there may be more emphasis on maximizing daylight.

Besides the differences between North and South, there are important differences between East and West. Time zones can be impractical big things and sunrise and sunset can look very different from their edges.

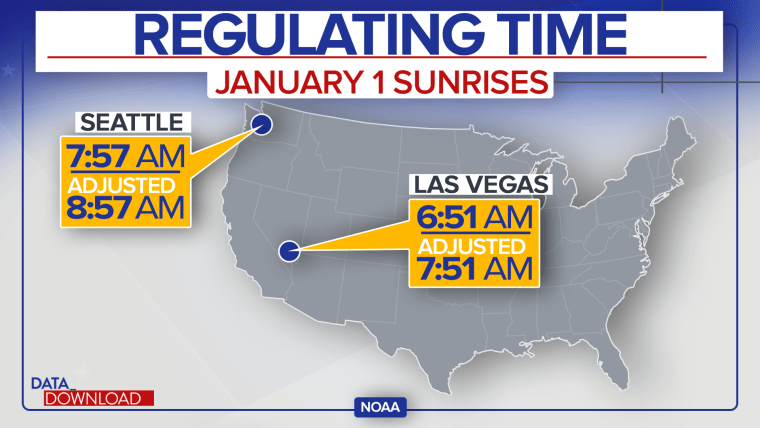

Consider some of the larger cities and how the switch to permanent summer time will affect them in the middle of winter.

On January 1 of this year, the sun rose in Las Vegas at 6:51 a.m., but in Seattle, on the country’s western edge and the Pacific time zone, the sun rose more than an hour later at 7:57. With permanent daylight saving time, the sun won’t rise in Seattle that day until about 9 a.m.

In the central time zone, the sun rose in Chicago at 7:18 a.m. to the west, in Minneapolis, it rose more than half an hour later. With permanent daylight saving time, it won’t go up in the Twin Cities until around 9am again

And in the large and wide eastern time zone, the differences are even more pronounced. Take, for example, Boston and Detroit, both of which are north of latitude 42. On January 1, in Boston this year, the sun rose at 7:13 a.m., but rose in Detroit at 8:01. This means that with permanent daylight saving time, Motor City won’t see the sun on January 1st until 9am

The late sunrises raise questions about the safety of children going to school in the morning, walking or standing at bus stops (a concern when the nation first tried permanent daylight saving time), and it means that cities on the western fringes of time zones are perhaps going to consider Morning rush hour in the dark.

So, yes, in a political world where stalemate is the norm, it’s nice to see the Senate meet on anything, especially unanimous. But the United States is a big country and in fact, there are large swaths of the nation where the Sun Protection Act may also be called the Rising In The Dark Act.

[ad_2]