Written by Ingrid K. Williams

Imagine a quick and easy test such as taking your body temperature or taking your blood pressure that can reliably identify an anxiety disorder or predict an impending depressive episode.

Health care providers have many tools for measuring a patient’s physical condition, but there are no reliable biomarkers–objective indicators of medical conditions observed from outside the patient–to assess mental health.

But some AI researchers now believe that your voice may be the key to understanding your mental state — and AI is well-suited to detecting such changes, which would be difficult, if not impossible, to perceive otherwise. The result is a suite of online apps and tools designed to track your mental state, as well as software that delivers real-time mental health assessments to telehealth providers and call centers.

Psychologists have long known that some mental health problems can be detected not just by listening to what a person says but how they say it, said Maria Espinola, a psychologist and assistant professor at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine.

For depressed patients, Espinola said, “their speech is generally more monotone, flatter, and softer. They also have a lower vocal range and lower volume. They take more pauses. They stop more often.”

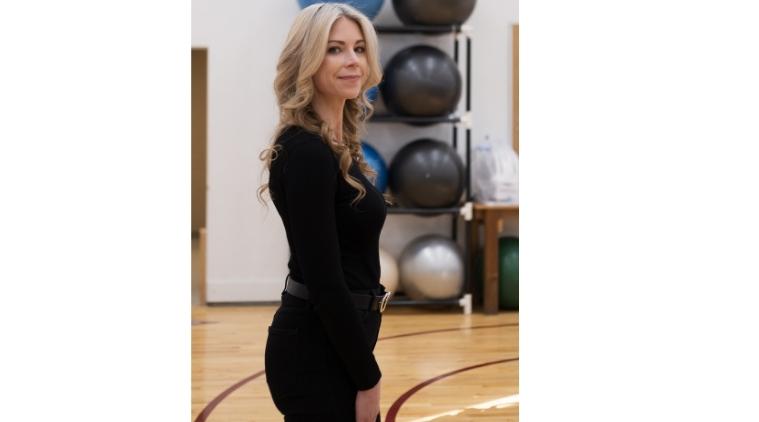

In her new book, Jennifer Hayes blends personal experience with the latest science on how exercise can improve your mental health. (Gabriela Bhaskar/The New York Times)

In her new book, Jennifer Hayes blends personal experience with the latest science on how exercise can improve your mental health. (Gabriela Bhaskar/The New York Times)

She said patients with anxiety feel more tension in their bodies, which may also change the way they sound. “They tend to talk faster. They have more trouble breathing.”

Today, machine learning researchers are taking advantage of these types of audio traits to predict depression and anxiety, as well as other mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder. Using deep learning algorithms can reveal additional patterns and characteristics, as captured in short audio recordings, that may not be obvious even to trained experts.

“The technology we’re using now can extract potentially meaningful features that even the human ear can’t pick up,” said Kate Bentley, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and a clinical psychologist at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“There is a lot of excitement about finding one or more objective biomarkers for psychiatric diagnoses that goes beyond more traditional forms of subjective assessment, such as physician-rated interviews or self-report measures,” she said. Other evidence that researchers track includes changes in activity levels, sleep patterns, and social media data.

These technological advances come at a time when mental health care is especially urgently needed. According to a report by the National Alliance on Mental Illness, 1 in 5 adults in the United States experienced a mental illness in 2020. The numbers continue to rise.

Although AI technology cannot address the dearth of qualified mental health care providers — there is almost not enough to meet the country’s needs, Bentley said — there is hope that it may reduce barriers to receiving correct diagnoses, and help clinicians identify patients who May be reluctance to seek care and facilitate self-monitoring between visits.

“A lot can happen between appointments, and technology can really offer us the potential to improve monitoring and evaluation in a more continuous way,” Bentley said.

To test this new technology, I started by downloading the Mental Fitness app from Sonde Health, a health tech company, to see if my feelings of distress were a sign of something serious or if I was feeling down. Describing the free app as a “sound-powered mental fitness tracker and diary,” he invited me to record my first recording, a 30-second oral journal entry, which would rank my mental health on a scale of 1 to 100.

A minute later, I got my score: not great 52. “Pay attention” the app warned.

The app indicated that the level of vitality detected in my voice was significantly low. Did I look monotonous just because I was trying to speak softly? Should I respond to the app’s suggestions to improve my mental fitness by going for a walk or organizing my space? (The first question might indicate one potential flaw with the app: As a consumer, it can be hard to figure out why your audio levels fluctuate.)

Later, after getting nervous between interviews, I tested another audio analysis program that focuses on detecting anxiety levels. The StressWaves Test is a free online tool from Cigna, the healthcare and insurance group, developed in collaboration with artificial intelligence specialist Ellipsis Health to assess stress levels using 60-second samples of recorded speech.

“What keeps you awake at night?” The site was directed. After I had spent a minute listing my persistent fears, the program recorded my recording and sent me an email saying, “Your stress level is moderate.” Unlike the Sonde app, Cigna’s email didn’t offer any helpful self-improvement tips.

Other technologies add a potentially beneficial layer of human interaction, such as Kintsugi, a Berkeley, California-based company, which recently raised $20 million in Series A funding. Kintsugi is named after the Japanese practice of repairing broken pottery with veins of gold.

Founded by Grace Chang and Rima Seiilova-Olson, who have linked past shared experience in the fight for access to mental health care, Kintsugi has developed technology for telehealth providers and call centers that can help them identify patients who might benefit from more support.

Using the Kintsugi voice analysis software, a nurse, for example, might be asked to take an extra minute to ask a perturbed parent with a colicky infant about their safety.

Jennifer Hayes, director of the NeuroFit Laboratory at McMaster University, at the school in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, March 12, 2022. (Narisa Ladak/The New York Times)

Jennifer Hayes, director of the NeuroFit Laboratory at McMaster University, at the school in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, March 12, 2022. (Narisa Ladak/The New York Times)

One concern with developing these types of machine learning technologies is the issue of bias — ensuring that programs work equitably for all patients, regardless of age, gender, race, nationality, and other demographic criteria.

“For machine learning models to work well, you really need a very large, diverse, powerful set of data,” Zhang said, noting that Kintsugi has used audio recordings from around the world, in many different languages, to guard against this particular problem.

Bentley said another major concern in this emerging field is privacy — particularly audio data, which can be used to identify individuals.

And even when patients agree to enroll, the issue of consent is sometimes twofold. In addition to assessing a patient’s mental health, some audio analysis programs use recordings to develop and refine their algorithms.

Another challenge, Bentley said, is potential consumers’ mistrust of machine learning and so-called black box algorithms, which work in ways that even developers themselves can’t fully explain — particularly the features they use to make predictions.

“There is the creation of the algorithm, there is the understanding of the algorithm,” said Dr. Alexander Young, interim director of the Simmel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior and chair of psychiatry at UCLA. In general: This is little, if any, human supervision present during the training phase of the program.

For now, Young remains cautiously optimistic about the potential of voice analysis techniques, particularly as tools for patients to monitor themselves.

“I think you can model people’s mental health status or approximate their mental health status in a general way,” he said. “People like to be able to monitor their condition themselves, especially with chronic diseases.”

But before automated voice analysis techniques enter mainstream use, some are calling for rigorous investigations into their accuracy.

“We really need more validation not just of voice technology, but of AI and machine learning models built on other data streams,” Bentley said. “And we need to achieve this validation in large-scale, well-designed, representative studies.”

Until then, AI-driven voice analysis technology remains a promising but unproven tool, and may ultimately be an everyday way to measure the temperature of our mental health.

This article originally appeared in the New York Times.

.

[ad_2]