A new study shows that global warming may cause birds to change their nesting habits, finding that some species in Chicago lay their eggs, on average, about a month earlier than usual.

The findings, published Friday in the Journal of Animal Ecology, add to a growing body of research on how birds are affected by changes in their environment and the potential struggles they may face in adapting to climate change.

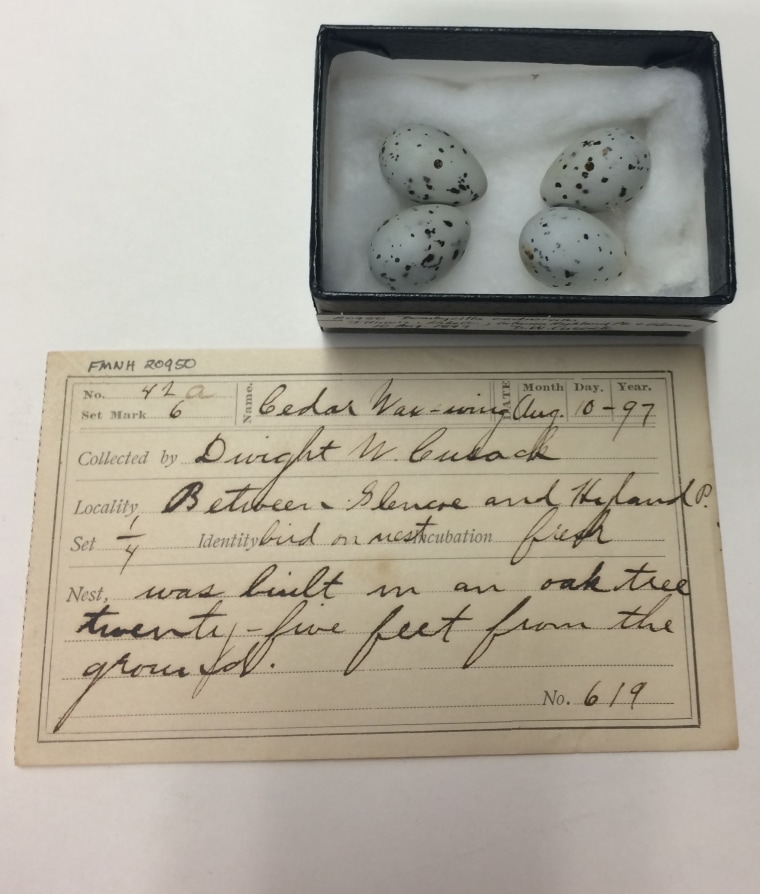

Research on bird nesting practices has combined extensive collections of eggs preserved in museums with recent observations to compare how egg-laying has changed over time. Scientists studied 72 species of birds for which historical and recent data were available in the Chicago area and found that about a third of them nest and lay eggs, on average, 25 days earlier than they did 100 years ago.

Field Museum

To study the cause of this shift, researchers studied atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations over the past 150 years, along with long-term temperature trends, and found that overall increases in both correlated with fluctuations in egg-laying dates for many. – Although not all kinds of birds.

“This really highlights the complexity of what climate change means for bird biology,” said John Bates, curator of birds at Chicago’s Field Museum and lead author of the study.

Bates said it’s not yet clear which bird species might be most at risk — or even what that vulnerability implies. It is possible, for example, that one consequence of nesting earlier than usual could be forcing some birds to compete for food and other resources in new ways, he said.

“If these birds are nesting early and earlier, one of the questions you have to ask is: Does this put them in a situation where there are not enough insects for them to eat?” Bates said.

Shifts in birds’ nesting habits are likely just one part of a series of changes in the ecosystem as a result of global warming, said Brock Bateman, director of climate sciences at the National Audubon Society, who was not involved in the study.

“Birds have to adapt to climate change by changing things up in time and space,” Pittman said. “They have to adjust the timing of things but also where they are across the landscape. That’s a lot to adapt to.”

As such, climate change may disturb different stages of a bird’s life cycle, from its migration patterns to where and when it breeds and builds nests in the spring.

If the birds start nesting earlier than usual, they run the risk of laying eggs during what climatologists refer to as “false spring,” or a short period of unusually warm weather in late winter that can trick hibernating plants and animals She thinks it’s the start of a new season. Birds, plants and other animals are then exposed to subsequent cold waves that can occur before the actual onset of spring, Pittman said, adding that insects are also affected by false springs.

“Ninety-six percent of wild birds feed their young insects to survive, so a sudden cold in these early springs can be really detrimental,” she said.

Robin Bailey, a wildlife biologist at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, who was not involved in the study, said the new findings are in line with other research on shifts in birds’ nesting habits, but emphasized the need for a variety of studies in order to determine how birds respond to changes. in her environment.

“When you think about all the cues that birds get — from climate, temperature, pollution, competition with other birds — they’re all acting on birds at the same time, and it’s really hard to differentiate the specific thing that’s responsible for what is responsible for it,” said Bailey, project leader for Cornell’s NestWatch. It is a nationwide Nest Monitoring Program that has been collecting data since the 1960s, “Biological Findings We See”.

While there are differences between bird species, Bailey said studying birds in their individual habitats can provide clues about larger, often related changes in their ecosystem.

In 2019, a study published in Ecology Letters found that birds’ body sizes are shrinking as global temperatures and climate warming increase, while their wings have grown in length, which may indicate the ways in which birds are adapting to climate change. That same year, a disturbing study published in Science found that nearly 3 billion birds have been lost in the United States and Canada since 1970.

Bates said this expanding field of research will be even more important as the effects of climate change are being felt in habitats around the world.

“Birds are definitely a harbinger of what’s going on,” he said. “They are related a lot more to what happens seasonally than we are. So I think closing the loop in bird life history is something we need to spend more time getting basic natural history data to do.”

[ad_2]